Materialism and Empirio-criticism

Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy

Chapter 5. The Recent Revolution in Natural Science and Philosophical Idealism

A year ago, in Die Neue Zeit (1906–07, No. 52), there appeared an article by Joseph Diner-Dénes entitled "Marxism and the Recent Revolution in the Natural Sciences." The defect of this article is that it ignores the epistemological conclusions which are being drawn from the "new" physics and in which we are especially interested at present. But it is precisely this defect which renders the point of view and the conclusions of the author particularly interesting for us. Joseph Diner-Dénes, like the present writer, holds the view of the "rank-and-file Marxist," of whom our Machians speak with such haughty contempt. For instance, Mr. Yushkevich writes that "ordinarily, the average rank-and-file Marxist calls himself a dialectical materialist" (p. 1 of his book). And now this rank-and-file Marxist, in the person of J. Diner-Dénes, has directly compared the recent discoveries in science, and especially in physics (X-rays, Becquerel rays, radium, etc.[1]), with Engels' Anti-Dühring. To what conclusion has this comparison led him? "In the most varied fields of natural science," writes Diner-Dénes, "new knowledge has been acquired, all of which tends towards that single point which Engels desired to make clear, namely, that in nature 'there are no irreconcilable contradictions, no forcibly fixed boundary lines and distinctions,' and that if contradictions and distinctions are met with in nature, it is because we alone have introduced their rigidity and absoluteness into nature." It was discovered, for instance, that light and electricity are only manifestations of one and the same force of nature.[2] Each day it becomes more probable that chemical affinity may be reduced to electrical processes. The indestructible and non-disintegrable elements of chemistry, whose number continues to grow as though in derision of the unity of the world, now prove to be destructible and disintegrable. The element radium has been converted into the element helium.[3] "Just as all the forces of nature have been reduced to one force, so all substances in nature have been reduced to one substance" (Diner-Dénes' italics). Quoting the opinion of one of the writers who regard the atom as only a condensation of the ether,[4] the author exclaims: "How brilliantly does this confirm the statement made by Engels thirty years ago that motion is the mode of existence of matter." "All phenomena of nature are motion, and the differences between them lie only in the fact that we human beings perceive this motion in different forms. . . . It is as Engels said. Nature, like history, is subject to the dialectical law of motion."

On the other hand, you cannot take up any of the writings of the Machians or about Machism without encountering pretentious references to the new physics, which is said to have refuted materialism, and so on and so forth. Whether these assertions are well-founded is another question, but the connection between the new physics, or rather a definite school of the new physics, and Machism and other varieties of modern idealist philosophy is beyond doubt. To analyse Machism and at the same time to ignore this connection—as Plekhanov does[5]—is to scoff at the spirit of dialectical materialism, i.e., to sacrifice the method of Engels to the letter of Engels. Engels says explicitly that "with each epoch making discovery even in the sphere of natural science ["not to speak of the history of mankind"], materialism has to change its form" (Ludwig Feuerbach, Germ. ed., p. 19).[6] Hence, a revision of the "form" of Engels' materialism, a revision of his natural-philosophical propositions is not only not "revisionism," in the accepted meaning of the term, but, on the contrary, is demanded by Marxism. We criticise the Machians not for making such a revision, but for their purely revisionist trick of betraying the essence of materialism under the guise of criticising its form and of adopting the fundamental precepts of reactionary bourgeois philosophy without making the slightest attempt to deal directly, frankly and definitely with assertions of Engels' which are unquestionably extremely important to the given question, as, for example, his assertion that ". . . motion without matter is unthinkable" (Anti-Dühring, p. 50).[7]

It goes without saying that in examining the connection between one of the schools of modern physicists and the rebirth of philosophical idealism, it is far from being our intention to deal with specific physical theories. What interests us exclusively is the epistemological conclusions that follow from certain definite propositions and generally known discoveries. These epistemological conclusions are of themselves so insistent that many physicists are already reaching for them. What is more, there are already various trends among the physicists, and definite schools are beginning to be formed on this basis. Our object, therefore, will be confined to explaining clearly the essence of the difference between these various trends and the relation in which they stand to the fundamental lines of philosophy.

← Chapter 5.1 →

1. The Crisis in Modern Physics

In his book Valeur de la science [Value of Science], the famous French physicist Henri Poincaré says that there are "symptoms of a serious crisis" in physics, and he devotes a special chapter to this crisis (Chap. VIII, cf. p. 171). The crisis is not confined to the fact that "radium, the great revolutionary," is undermining the principle of the conservation of energy. "All the other principles are equally endangered" (p. 180). For instance, Lavoisier's principle, or the principle of the conservation of mass, has been undermined by the electron theory of matter. According to this theory atoms are composed of very minute particles called electrons, which are charged with positive or negative electricity and "are immersed in a medium which we call the ether." The experiments of physicists provide data for calculating the velocity of the electrons and their mass (or the relation of their mass to their electrical charge). The velocity proves to be comparable with the velocity of light (300,000 kilometres per second), attaining, for instance, one-third of the latter. Under such circumstances the twofold mass of the electron has to be taken into account, corresponding to the necessity of over coming the inertia, firstly, of the electron itself and, secondly, of the ether. The former mass will be the real or mechanical mass of the electron, the latter the "electrodynamic mass which represents the inertia of the ether." And it turns out that the former mass is equal to zero. The entire mass of the electrons, or, at least, of the negative electrons, proves to be totally and exclusively electrodynamic in its origin.[8] Mass disappears. The foundations of mechanics are undermined. Newton's principle, the equality of action and reaction, is undermined, and so on.

We are faced, says Poincaré, with the "ruins" of the old principles of physics, "a general debacle of principles." It is true, he remarks, that all the mentioned departures from principles refer to infinitesimal magnitudes; it is possible that we are still ignorant of other infinitesimals counteracting the undermining of the old principles. Moreover, radium is very rare. But at any rate we have reached a "period of doubt." We have already seen what epistemological deductions the author draws from this "period of doubt": "it is not nature which imposes on [or dictates to] us the concepts of space and time, but we who impose them on nature"; "whatever is not thought, is pure nothing." These deductions are idealist deductions. The breakdown of the most fundamental principles shows (such is Poincaré's trend of thought) that these principles are not copies, photographs of nature, not images of something external in relation to man's consciousness, but products of his consciousness. Poincaré does not develop these deductions consistently, nor is he essentially interested in the philosophical aspect of the question. It is dealt with in detail by the French writer on philosophical problems, Abel Rey, in his book The Physical Theory of the Modern Physicists (La Théorie physique chez les physiciens contemporains, Paris, F. Alcan, 1907). True, the author himself is a positivist, i.e., a muddlehead and a semi-Machian, but in this case this is even a certain advantage, for he can not be suspected of a desire to "slander" our Machians' idol. Rey cannot be trusted when it comes to giving an exact philosophical definition of concepts and of materialism in particular, for Rey too is a professor, and as such is imbued with an utter contempt for the materialists (and distinguishes himself by utter ignorance of the epistemology of materialism). It goes without saying that a Marx or an Engels is absolutely non-existent for such "men of science." But Rey summarises carefully and in general conscientiously the extremely abundant literature on the subject, not only French, but English and German as well (Ostwald and Mach in particular), so that we shall have frequent recourse to his work.

The attention of philosophers in general, says the author, and also of those who, for one reason or another, wish to criticise science generally, has now been particularly attracted towards physics. "In discussing the limits and value of physical knowledge, it is in effect the legitimacy of positive science, the possibility of knowing the object, that is criticised" (pp. i-ii). From the "crisis in modern physics" people hasten to draw sceptical conclusions (p. 14). Now, what is this crisis? During the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century the physicists agreed among themselves on everything essential. They believed in a purely mechanical explanation of nature: they assumed that physics is nothing but a more complicated mechanics, namely, a molecular mechanics. They differed only as to the methods used in reducing physics to mechanics and as to the details of the mechanism. . . . At present the spectacle presented by the physico-chemical sciences seems completely changed. Extreme disagreement has replaced general unanimity, and no longer does it concern details, but leading and fundamental ideas. While it would be an exaggeration to say that each scientist has his own peculiar tendencies, it must nevertheless be noted that science, and especially physics, has, like art, its numerous schools, the conclusions of which often differ from, and sometimes are directly opposed and hostile to each other. . . .

"From this one may judge the significance and scope of what has been called the crisis in modern physics.

"Down to the middle of the nineteenth century, traditional physics had assumed that it was sufficient merely to extend physics in order to arrive at a metaphysics of matter. This physics ascribed to its theories an ontological value. And its theories were all mechanistic. The traditional mechanism [Rey employs this word in the specific sense of a system of ideas which reduces physics to mechanics] thus claimed, over and above the results of experience, a real knowledge of the material universe. This was not a hypothetical account of experience; it was a dogma. . ." (p. 16).

We must here interrupt the worthy "positivist." It is clear that he is describing the materialist philosophy of traditional physics but does not want to call the devil (materialism) by name. Materialism to a Humean must appear to be metaphysics, dogma, a transgression of the bounds of experience, and so forth. Knowing nothing of materialism, the Humean Rey has no conception whatever of dialectics, of the difference between dialectical materialism and metaphysical materialism, in Engels' meaning of the term. Hence, the relation between absolute and relative truth, for example, is absolutely unclear to Rey.

". . . The criticism of traditional mechanism made during the whole of the second half of the nineteenth century weakened the premise of the ontological reality of mechanism. On the basis of these criticisms a philosophical conception of physics was founded which became almost traditional in philosophy at the end of the nineteenth century. Science was nothing but a symbolic formula, a method of notation (repérage, the creation of signs, marks, symbols), and since the methods of notation varied according to the schools, the conclusion was soon reached that only that was denoted which had been previously designed (façonné) by man for notation (or symbolisation). Science became a work of art for dilettantes, a work of art for utilitarians: views which could with legitimacy be generally interpreted as the negation of the possibility of science. A science which is a pure artifice for acting upon nature, a mere utilitarian technique, has no right to call itself science, without perverting the meaning of words. To say that science can be nothing but such an artificial means of action is to disavow science in the proper meaning of the term.

"The collapse of traditional mechanism, or, more precisely, the criticism to which it was subjected, led to the proposition that science itself had also collapsed. From the impossibility of adhering purely and simply to traditional mechanism it was inferred that science was impossible" (pp. 16-17).

And the author asks: "Is the present crisis in physics a temporary and external incident in the evolution of science, or is science itself making an abrupt right-about-face and definitely abandoning the path it has hitherto pursued?. . ."

"If the [physical and chemical] sciences, which in history have been essentially emancipators, collapse in this crisis, which reduces them to the status of mere, technically useful recipes but deprives them of all significance from the stand point of knowledge of nature, the result must needs be a complete revolution both in the art of logic and the history of ideas. Physics then loses all educational value; the spirit of positive science it represents becomes false and dangerous." Science can offer only practical recipes but no real knowledge. "Knowledge of the real must be sought and given by other means. . . . One must take another road, one must return to subjective intuition, to a mystical sense of reality, in a word, to the mysterious, all that of which one thought it had been deprived" (p. 19).

As a positivist, the author considers such a view wrong and the crisis in physics only temporary. We shall presently see how Rey purifies Mach, Poincaré and Co. of these conclusions. At present we shall confine ourselves to noting the fact of the "crisis" and its significance. From the last words of Rey quoted by us it is quite clear what reactionary elements have taken advantage of and aggravated this crisis. Rey explicitly states in the preface to his work that "the fideist and anti-intellectualist movement of the last years of the nineteenth century" is seeking "to base itself on the general spirit of modern physics" (p. ii). In France, those who put faith above reason are called fideists (from the Latin fides, faith). Anti-intellectualism is a doctrine that denies the rights or claims of reason. Hence, in its philosophical aspect, the essence of the "crisis in modern physics" is that the old physics regarded its theories as "real knowledge of the material world," i.e., a reflection of objective reality. The new trend in physics regards theories only as symbols, signs, and marks for practice, i.e., it denies the existence of an objective reality independent of our mind and reflected by it. If Rey had used correct philosophical terminology, he would have said: the materialist theory of knowledge, instinctively accepted by the earlier physics, has been replaced by an idealist and agnostic theory of knowledge, which, against the wishes of the idealists and agnostics, has been taken advantage of by fideism.

But Rey does not present this replacement, which constitutes the crisis, as though all the modern physicists stand opposed to all the old physicists. No. He shows that in their epistemological trends the modern physicists are divided into three schools: the energeticist or conceptualist school; the mechanistic or neo-mechanistic school, to which the vast majority of physicists still adhere; and in between the two, the critical school. To the first belong Mach and Duhem; to the third, Henri Poincaré to the second, Kirchhoff, Helmholtz, Thomson (Lord Kelvin), Maxwell—among the older physicists—and Larmor and Lorentz among the modern physicists. What the essence of the two basic trends is (for the third is not independent, but intermediate) may be judged from the following words of Rey's:

"Traditional mechanism constructed a system of the material world." Its doctrine of the structure of matter was based on "elements qualitatively homogenous and identical"; and elements were to be regarded as "immutable, impenetrable," etc. Physics "constructed a real edifice out of real materials and real cement. The physicist possessed material elements, the causes and modes of their action, and the real laws of their action" (pp. 33-38). "The change in this view consists in the rejection of the ontological significance of the theories and in an exaggerated emphasis on the phenomenological significance of physics." The conceptualist view operates with "pure abstractions . . . and seeks a purely abstract theory which will as far as possible eliminate the hypothesis of matter. . . . The notion of energy thus becomes the substructure of the new physics. This is why conceptualist physics may most often be called energeticist physics," although this designation does not fit, for example, such a representative of conceptualist physics as Mach (p. 46).

Rey's identification of energetics with Machism is not altogether correct, of course; nor is his assurance that the neo-mechanistic school as well is approaching a phenomenalist view of physics (p. 48), despite the profundity of its disagreement with the conceptualists. Rey's "new" terminology does not clarify, but rather obscures matters; but we could not avoid it if we were to give the reader an idea of how a "positivist" regards the crisis in physics. Essentially, the opposition of the "new" school to the old views fully coincides, as the reader may have convinced himself, with Kleinpeter's criticism of Helmholtz quoted above. In his presentation of the views of the various physicists Rey reflects the indefiniteness and vacillation of their philosophical views. The essence of the crisis in modern physics consists in the breakdown of the old laws and basic principles, in the rejection of an objective reality existing outside the mind, that is, in the replacement of materialism by idealism and agnosticism. "Matter has disappeared"—one may thus express the fundamental and characteristic difficulty in relation to many of the particular questions, which has created this crisis. Let us pause to discuss this difficulty.

← Chapter 5.2 →

2. "Matter Has Disappeared"

Such, literally, is the expression that may be encountered in the descriptions given by modern physicists of recent discoveries. For instance, L. Houllevigue, in his book The Evolution of the Sciences, entitles his chapter on the new theories of matter: "Does Matter Exist?" He says: "The atom dematerialises, matter disappears."[9] To see how easily fundamental philosophical conclusions are drawn from this by the Machians, let us take Valentinov. He writes: "The statement that the scientific explanation of the world can find a firm foundation only in materialism is nothing but a fiction, and what is more, an absurd fiction" (p. 67). He quotes as a destroyer of this absurd fiction Augusto Righi, the well-known Italian physicist, who says that the electron theory "is not so much a theory of electricity as of matter; the new system simply puts electricity in the place of matter." (Augusto Righi, Die moderne Theorie der physikalischen Erscheinungen, [The Modern Theory of Physical Phenomena], Leipzig, 1905, S. 131. There is a Russian translation.) Having quoted these words (p. 64), Mr. Valentinov exclaims:

"Why does Righi permit himself to commit this offence against sacred matter? Is it perhaps because he is a solipsist, an idealist, a bourgeois criticist, an empirio-monist, or even someone worse?"

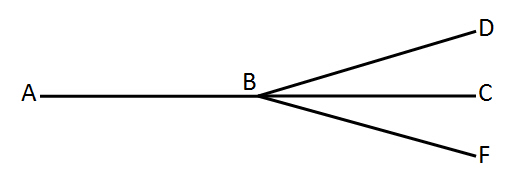

This remark, which seems to Mr. Valentinov to annihilate the materialists by its sarcasm, only discloses his virgin innocence on the subject of philosophical materialism. Mr. Valentinov has no suspicion of the real connection between philosophical idealism and the "disappearance of matter." The "disappearance of matter" of which he speaks, in imitation of the modern physicists, has no relation to the epistemological distinction between materialism and idealism. To make this clear, let us take one of the most consistent and clearest of the Machians, Karl Pearson. For him the physical universe consists of groups of sense-impressions. He illustrates "our conceptual model of the physical universe" by the following diagram, explaining, however, that it takes no account of relative sizes (The Grammar of Science, p. 282):–

In order to simplify his diagram, Karl Pearson entirely omits the question of the relation between ether and electricity, or positive electrons and negative electrons. But that is not important. What is important is that from Pearson's idealist standpoint "bodies" are first regarded as sense-impressions, and then the constitution of these bodies out of particles, particles out of molecules and so forth affects the changes in the model of the physical world, but in no way affects the question of whether bodies are symbols of perceptions, or perceptions images of bodies. Materialism and idealism differ in their respective answers to the question of the source of our knowledge and of the relation of knowledge (and of the "mental" in general) to the physical world; while the question of the structure of matter, of atoms and electrons, is a question that concerns only this "physical world." When the physicists say that "matter is disappearing," they mean that hitherto science reduced its investigations of the physical world to three ultimate concepts: matter, electricity and ether; whereas now only the two latter remain. For it has become possible to reduce matter to electricity; the atom can be explained as resembling an infinitely small solar system, within which negative electrons[11] move around a positive electron[12] with a definite (and, as we have seen, enormously large) velocity. It is consequently possible to reduce the physical world from scores of elements to two or three elements (inasmuch as positive and negative electrons constitute "two essentially distinct kinds of matter," as the physicist Pellat says—Rey, op. cit., pp. 294-95). Hence, natural science leads to the "unity of matter" (ibid.)[10] —such is the real meaning of the statement regarding the disappearance of matter, its replacement by electricity, etc., which is leading so many people astray. "Matter is disappearing" means that the limit within which we have hitherto known matter is vanishing and that our knowledge is penetrating deeper; properties of matter are likewise disappearing which formerly seemed absolute, immutable, and primary (impenetrability, inertia, mass,[13] etc.) and which are now revealed to be relative and characteristic only of certain states of matter. For the sole "property" of matter with whose recognition philosophical materialism is bound up is the property of being an objective reality, of existing outside our mind.

The error of Machism in general, as of the Machian new physics, is that it ignores this basis of philosophical materialism and the distinction between metaphysical materialism and dialectical materialism. The recognition of immutable elements, "of the immutable substance of things," and so forth, is not materialism, but metaphysical, i.e., anti-dialectical, materialism. That is why J. Dietzgen emphasised that the "subject-matter of science is endless," that not only the in finite, but the "smallest atom" is immeasurable, unknowable to the end, inexhaustible, "for nature in all her parts has no beginning and no end" (Kleinere philosophische Schriften, S. 229-30). That is why Engels gave the example of the discovery of alizarin in coal tar and criticised mechanical materialism. In order to present the question in the only correct way, that is, from the dialectical materialist standpoint, we must ask: Do electrons, ether and so on exist as objective realities outside the human mind or not? The scientists will also have to answer this question unhesitatingly; and they do invariably answer it in the affirmative, just as they unhesitatingly recognise that nature existed prior to man and prior to organic matter. Thus, the question is decided in favour of materialism, for the concept matter, as we already stated, epistemologically implies nothing but objective reality existing independently of the human mind and renected by it.

But dialectical materialism insists on the approximate, relative character of every scientific theory of the structure of matter and its properties; it insists on the absence of absolute boundaries in nature, on the transformation of moving matter from one state into another, which is to us apparently irreconcilable with it, and so forth. However bizarre from the standpoint of "common sense" the transformation of imponderable ether into ponderable matter and vice versa may appear, however "strange" may seem the absence of any other kind of mass in the electron save electromagnetic mass, however extraordinary may be the fact that the mechanical laws of motion are confined only to a single sphere of natural phenomena and are subordinated to the more profound laws of electromagnetic phenomena, and so forth—all this is but another corroboration of dialectical materialism. It is mainly because the physicists did not know dialectics that the new physics strayed into idealism. They combated metaphysical (in Engels', and not the positivist, i.e., Humean, sense of the word) materialism and its one-sided "mechanism," and in so doing threw the baby out with the bath-water. Denying the immutability of the elements and the properties of matter known hitherto, they ended in denying matter, i.e., the objective reality of the physical world. Denying the absolute character of some of the most important and basic laws, they ended in denying all objective law in nature and in declaring that a law of nature is a mere convention, "a limitation of expectation," "a logical necessity," and so forth. Insisting on the approximate and relative character of our knowledge, they ended in denying the object independent of the mind and reflected approximately-correctly and relatively-truthfully by the mind. And so on, and so forth, without end.

The opinions expressed by Bogdanov in 1899 regarding "the immutable essence of things," the opinions of Valentinov and Yushkevich regarding "substance," and so forth—are similar fruits of ignorance of dialectics. From Engels' point of view, the only immutability is the reflection by the human mind (when there is a human mind) of an external world existing and developing independently of the mind. No other "immutability," no other "essence," no other "absolute substance," in the sense in which these concepts were depicted by the empty professorial philosophy, exist for Marx and Engels. The "essence" of things, or "substance," is also relative; it expresses only the degree of profundity of man's knowledge of objects; and while yesterday the profundity of this knowledge did not go beyond the atom, and today does not go beyond the electron and ether, dialectical materialism insists on the temporary, relative, approximate character of all these milestones in the knowledge of nature gained by the progressing science of man. The electron is as inexhaustible as the atom, nature is infinite, but it infinitely exists. And it is this sole categorical, this sole unconditional recognition of nature's existence outside the mind and perception of man that distinguishes dialectical materialism from relativist agnosticism and idealism.

Let us cite two examples of the way in which the new physics wavers unconsciously and instinctively between dialectical materialism, which remains unknown to the bourgeois scientists, and "phenomenalism," with its inevitable subjectivist (and, subsequently, directly fideist) deductions.

This same Augusto Righi, from whom Mr. Valentinov was unable to get a reply on the question which interested him about materialism, writes in the introduction to his book: "What the electrons, or electrical atoms, really are remains even now a mystery; but in spite of this, the new theory is perhaps destined in time to achieve no small philosophical significance, since it is arriving at entirely new hypotheses regarding the structure of ponderable matter and is striving to reduce all phenomena of the external world to one common origin.

"For the positivist and utilitarian tendencies of our time such an advantage may be of small consequence, and a theory is perhaps regarded primarily as a means of conveniently ordering and summarising facts and as a guide in the search for further phenomena. But while in former times perhaps too much confidence was placed in the faculties of the human mind, and it was considered too easy to grasp the ultimate causes of all things, there is nowadays a tendency to fall into the opposite error" (op. cit., p. 3).

Why does Righi dissociate himself here from the positivist and utilitatian tendencies? Because, while apparently he has no definite philosophical standpoint, he instinctively clings to the reality of the external world and to the recognition that the new theory is not only a "convenience" (Poincaré), not only an "empirio-symbol" (Yushkevich), not only a "harmonising of experience" (Bogdanov), or whatever else they call such subjectivist fancies, but a further step in the cognition of objective reality. Had this physicist been acquainted with dialectical materialism, his opinion of the error which is the opposite of the old metaphysical materialism might perhaps have become the starting point of a correct philosophy. But these people's whole environment estranges them from Marx and Engels and throws them into the embrace of vulgar official philosophy.

Rey too is entirely unfamiliar with dialectics. But he too is compelled to state that among the modern physicists there are those who continue the traditions of "mechanism" (i.e., materialism). The path of "mechanism," says he, is pursued not only by Kirchhoff, Hertz, Boltzmann, Maxwell, Helmholtz and Lord Kelvin. "Pure mechanists, and in some respects more mechanist than anybody else, and representing the culmination (l'aboutissant) of mechanism, are those who follow Lorentz and Larmor in formulating an electrical theory of matter and who arrive at a denial of the constancy of mass, declaring it to be a function of motion. They are all mechanists because they take real motion as their starting point" (Rey's italics, pp. 290-91).

". . . If, for example, the recent hypotheses of Lorentz, Larmor and Langevin were, thanks to certain experimental confirmation, to obtain a sufficiently stable basis for the systematisation of physics, it would be certain that the laws of present-day mechanics are nothing but a corollary of the laws of electromagnetism: they would constitute a special case of the latter within well-defined limits. Constancy of mass and our principle of inertia would be valid only for moderate velocities of bodies, the term 'moderate' being taken in relation to our senses and to the phenomena which constitute our general experience. A general recasting of mechanics would result, and hence also, a general recasting of the systematisation of physics."

"Would this imply the abandonment of mechanism? By no means. The purely mechanist tradition would still be followed, and mechanism would follow its normal course of development" (p. 295).

"Electronic physics, which should be ranked among the theories of a generally mechanist spirit, tends at present to impose its systematisation on physics. Although the fundamental principles of this electronic physics are not furnished by mechanics but by the experimental data of the theory of electricity, its spirit is mechanistic, because: (1) It uses figurative (figurés), material elements to represent physical properties and their laws; it expresses itself in terms of perception. (2) While it no longer regards physical phenomena as particular cases of mechanical phenomena, it regards mechanical phenomena as particular cases of physical phenomena. The laws of mechanics thus retain their direct continuity with the laws of physics; and the concepts of mechanics remain concepts of the same order as physico-chemical concepts. In traditional mechanism it was motions copied (calqués) from relatively slow motions, which, since they alone were known and most directly observable, were taken. . . as a type of all possible motions. Recent experiments, on the contrary, show that it is necessary to extend our conception of possible motions. Traditional mechanics remains entirely intact, but it now applies only to relatively slow motions. . . . In relation to large velocities, the laws of motion are different. Matter appears to be reduced to electrical particles, the ultimate elements of the atom. . . . (3) Motion, displacement in space, remains the only figurative (figuré) element of physical theory. (4) Finally, what from the standpoint of the general spirit of physics comes before every other consideration is the fact that the conception of physics, its methods, its theories, and their relation to experience remains absolutely identical with the conception of mechanism, with the conception of physics held since the Renaissance" (pp. 46-47).

I have given this long quotation from Rey in full because owing to his perpetual anxiety to avoid "materialist metaphysics," it would have been impossible to expound his statements in any other way. But however much both Rey and the physicists of whom he speaks abjure materialism, it is nevertheless beyond question that mechanics was a copy of real motions of moderate velocity, while the new physics is a copy of real motions of enormous velocity. The recognition of theory as a copy, as an approximate copy of objective reality, is materialism. When Rey says that among modern physicists there "is a reaction against the conceptualist [Machian] and energeticist school," and when he ranks the physicists of the electron theory among the representatives of this reaction (p. 46), we could desire no better corroboration of the fact that the struggle is essentially between the materialist and the idealist tendencies. But we must not forget that, apart from the general prejudices against materialism common to all educated philistines, the most outstanding theoreticians are handicapped by a complete ignorance of dialectics.

← Chapter 5.3 →

3. Is Motion Without Matter Conceivable?

The fact that philosophical idealism is attempting to make use of the new physics, or that idealist conclusions are being drawn from the latter, is due not to the discovery of new kinds of substance and force, of matter and motion, but to the fact that an attempt is being made to conceive motion without matter. And it is the essence of this attempt which our Machians fail to examine. They were unwilling to take account of Engels' statement that "motion without matter is unthinkable." J. Dietzgen in 1869, in his The Nature of tbe Workings of the Human Mind, expressed the same idea as Engels, although, it is true, not without his usual muddled attempts to "reconcile" materialism and idealism. Let us leave aside these attempts, which are to a large extent to be explained by the fact that Dietzgen is arguing against Büchner's non-dialectical materialism, and let us examine Dietzgen's own statements on the question under consideration. He says: "They [the idealists] want to have the general without the particular, mind without matter, force without substance, science without experience or material, the absolute without the relative" (Das Wesen der menschlichen Kopfarbeit, 1903, S. 108). Thus the endeavour to divorce motion from matter, force from substance, Dietzgen associates with idealism, compares with the endeavour to divorce thought from the brain. "Liebig," Dietzgen continues, "who is especially fond of straying from his inductive science into the field of speculation, says in the spirit of idealism: 'force cannot be seen'" (p. 109). "The spiritualist or the idealist believes in the spiritual, i.e., ghostlike and inexplicable, nature of force" (p. 110). "The antithesis between force and matter is as old as the antithesis between idealism and materialism" (p. 111). "Of course, there is no force without matter, no matter without force; forceless matter and matterless force are absurdities. If there are idealist natural scientists who believe in the immaterial existence of forces, on this point they are not natural scientists. . . but seers of ghosts" (p. 114).

We thus see that scientists who were prepared to grant that motion is conceivable without matter were to be encountered forty years ago too, and that "on this point" Dietzgen declared them to be seers of ghosts. What, then, is the connection between philosophical idealism and the divorce of matter from motion, the separation of substance from force? Is it not "more economical," indeed, to conceive motion without matter?

Let us imagine a consistent idealist who holds that the entire world is his sensation, his idea, etc. (if we take "nobody's" sensation or idea, this changes only the variety of philosophical idealism but not its essence). The idealist would not even think of denying that the world is motion, i.e., the motion of his thoughts, ideas, sensations. The question as to what moves, the idealist will reject and regard as absurd: what is taking place is a change of his sensations, his ideas come and go, and nothing more. Outside him there is nothing. "It moves"—and that is all. It is impossible to conceive a more "economical" way of thinking. And no proofs, syllogisms, or definitions are capable of refuting the solipsist if he consistently adheres to his view.

The fundamental distinction between the materialist and the adherent of idealist philosophy consists in the fact that the materialist regards sensation, perception, idea, and the mind of man generally, as an image of objective reality. The world is the movement of this objective reality reflected by our consciousness. To the movement of ideas, perceptions, etc., there corresponds the movement of matter outside me. The concept matter expresses nothing more than the objective reality which is given us in sensation. Therefore, to divorce motion from matter is equivalent to divorcing thought from objective reality, or to divorcing my sensations from the external world—in a word, it is to go over to idealism. The trick which is usually performed in denying matter, and in assuming motion without matter, consists in ignoring the relation of matter to thought. The question is presented as though this relation did not exist, but in reality it is introduced surreptitiously; at the beginning of the argument it remains unexpressed, but subsequently crops up more or less imperceptibly.

Matter has disappeared, they tell us, wishing from this to draw epistemological conclusions. But has thought remained?—we ask. If not, if with the disappearance of matter thought has also disappeared, if with the disappearance of the brain and nervous system ideas and sensations, too, have disappeared—then it follows that everything has disappeared. And your argument has disappeared as a sample of "thought" (or lack of thought)! But if it has remained—if it is assumed that with the disappearance of matter, thought (idea, sensation, etc.) does not disappear, then you have surreptitiously gone over to the standpoint of philosophical idealism. And this always happens with people who wish, for "economy's sake," to conceive of motion without matter, for tacitly, by the very fact that they continue to argue, they are acknowledging the existence of thought after the disappearance of matter. This means that a very simple, or a very complex philosophical idealism is taken as a basis; a very simple one, if it is a case of frank solipsism (I exist, and the world is only my sensation); a very complex one, if instead of the thought, ideas and sensations of a living person, a dead abstraction is posited, that is, nobody's thought, nobody's idea, nobody's sensation, but thought in general (the Absolute Idea, the Universal Will, etc.), sensation as an indeterminate "element," the "psychical," which is substituted for the whole of physical nature, etc., etc. Thousands of shades of varieties of philosophical idealism are possible and it is always possible to create a thousand and first shade; and to the author of this thousand and first little system (empirio-monism, for example) what distinguishes it from the rest may appear to be momentous. From the standpoint of materialism, however, the distinction is absolutely unessential. What is essential is the point of departure. What is essential is that the attempt to think of motion without matter smuggles in thought divorced from matter—and that is philosophical idealism.

Therefore, for example, the English Machian Karl Pearson, the clearest and most consistent of the Machians, who is averse to verbal trickery, directly begins the seventh chapter of his book, devoted to "matter," with the characteristic heading "All things move—but only in conception." "It is therefore, for the sphere of perception, idle to ask what moves and why it moves" (The Grammar of Science, p. 243).

Therefore, too, in the case of Bogdanov, his philosophical misadventures in fact began before his acquaintance with Mach. They began from the moment he put his trust in the assertion of the eminent chemist, but poor philosopher, Ostwald, that motion can be thought of without matter. It is all the more fitting to pause on this long-past episode in Bogdanov's philosophical development since it is impossible when speaking of the connection between philosophical idealism and certain trends in the new physics to ignore Ostwald's "energetics."

"We have already said," wrote Bogdanov in 1899, "that the nineteenth century did not succeed in ultimately ridding itself of the problem of 'the immutable essence of things.' This essence, under the name of 'matter,' even holds an important place in the world outlook of the foremost thinkers of the century" (Fundamental Elements of the Historical Outlook on Nature, p. 38).

We said that this is a sheer muddle. The recognition of the objective reality of the outer world, the recognition of the existence outside our mind of eternally moving and eternally changing matter, is here confused with the recognition of the immutable essence of things. It is hardly possible that Bogdanov in 1899 did not rank Marx and Engels among the "foremost thinkers." But he obviously did not understand dialectical materialism.

". . . In the processes of nature two aspects are usually still distinguished: matter and-its motion. It cannot be said that the concept matter is distinguished by great clarity. It is not easy to give a satisfactory answer to the question—what is matter? It is defined as the 'cause of sensations' or as the 'permanent possibility of sensation'; but it is evident that matter is here confused with motion. . . ."

It is evident that Bogdanov is arguing incorrectly. Not only does he confuse the materialist recognition of an objective source of sensations (unclearly formulated in the words "cause of sensations") with Mill's agnostic definition of matter as the permanent possibility of sensation, but the chief error here is that the author, having boldly approached the question of the existence or non-existence of an objective source of sensations, abandons this question half-way and jumps to another question, the question of the existence or non-existence of matter without motion. The idealist may regard the world as the movement of our sensations (even though "socially organised" and "harmonised" to the highest degree); the materialist regards the world as the movement of an objective source, of an objective model of our sensations. The metaphysical, i.e., anti-dialectical, materialist may accept the existence of matter without motion (even though temporarily, before "the first impulse," etc.). The dialectical materialist not only regards motion as an inseparable property of matter, but rejects the simplified view of motion and so forth.

". . . The most exact definition would, perhaps, be the following: 'matter is what moves'; but this is as devoid of content as though one were to say that matter is the subject of a sentence, the predicate of which is 'moves.' The fact, most likely, is that in the epoch of statics men were wont to see something necessarily solid in the role of the subject, an 'object,' and such an inconvenient thing for statical thought as 'motion' they were prepared to tolerate only as a predicate, as one of the attributes of 'matter.'"

This is something like the charge Akimov brought against the Iskra-ists, namely, that their programme did not contain the word proletariat in the nominative case![17] Whether we say the world is moving matter, or that the world is material motion, makes no difference whatever.

" . . . But energy must have a vehicle—say those who believe in matter. Why?—asks Ostwald, and with reason. Must nature necessarily consist of subject and predicate?" (p. 39)

Ostwald's answer, which so pleased Bogdanov in 1899, is plain sophistry. Must our judgments necessarily consist of electrons and ether?—one might retort to Ostwald. As a matter of fact, the mental elimination from "nature" of matter as the "subject" only implies the tacit admission into philosophy of thought as the "subject" (i.e., as the primary, the starting point, independent of matter). Not the subject, but the objective source of sensation is eliminated, and sensation becomes the "subject," i.e., philosophy becomes Berke leian, no matter in what trappings the word "sensation" is afterwards decked. Ostwald endeavoured to avoid this inevitable philosophical alternative (materialism or idealism) by an indefinite use of the word "energy," but this very endeavour only once again goes to prove the futility of such artifices. If energy is motion, you have only shifted the difficulty from the subject to the predicate, you have only changed the question, does matter move? into the question, is energy material? Does the transformation of energy take place outside my mind, independently of man and mankind, or are these only ideas, symbols, conventional signs, and so forth? And this question proved fatal to the "energeticist" philosophy, that attempt to disguise old epistemological errors by a "new" terminology.

Here are examples of how the energeticist Ostwald got into a muddle. In the preface to his Lectures on Natural Philosophy[16] he declares that he regards "as a great gain the simple and natural removal of the old difficulties in the way of uniting the concepts matter and spirit by subordinating both to the concept energy." This is not a gain, but a loss, because the question whether epistemological investigation (Ostwald does not clearly realise that he is raising an epistemological and not a chemical issue!) is to be conducted along materialist or idealist lines is not being solved but is being confused by an arbitrary use of the term "energy." Of course, if we "subordinate" both matter and mind to this concept, the verbal annihilation of the antithesis is beyond question, but the absurdity of the belief in sprites and hobgoblins, for instance, is not removed by calling it "energetics." On page 394 of Ostwald's Lectures we read: "That all external events may be presented as an interaction of energies can be most simply explained if our mental processes are themselves energetic and impose (aufprägen) this property of theirs on all external phenornena." This is pure idealism: it is not our thought that reflects the transformation of energy in the external world, but the external world that reflects a certain "property" of our mind! The American philosopher Hibben, pointing to this and similar passages in Ostwald's Lectures, aptly says that Ostwald "appears in a Kantian disguise": the explicability of the phenomena of the external world is deduced from the properties of our mind! "It is obvious therefore," says Hibben, "that if the primary concept of energy is so defined as to embrace psychical phenomena, we have no longer the simple concept of energy as understood and recognised in scientific circles or among the Energetiker themselves...."[J. G. Hibben, "The Theory of Energetics and Its Philosophical Bearings," The Monist, Vol. XIII, No. 3, April 1903, pp. 329-30.] The transformation of energy is regarded by science as an objective process independent of the minds of men and of the experience of mankind, that is to say, it is regarded materialistically. And by energy, Ostwald himself in many instances, probably in the vast majority of instances, means material motion.

And this accounts for the remarkable phenomenon that Bogdanov, a disciple of Ostwald, having become a disciple of Mach, began to reproach Ostwald not because he does not adhere consistently to a materialistic view of energy, but because he admits the materialistic view of energy (and at times even takes it as his basis). The materialists criticise Ostwald because he lapses into idealism, because he attempts to reconcile materialism and idealism. Bogdanov criticises Ostwald from the idealist standpoint. In 1906 he wrote: ". . . Ostwald's energetics, hostile to atomism but for the rest closely akin to the old materialism, enlisted my heartiest sympathy. I soon noticed, however, an important contradiction in his Naturphilosohhie : although he frequently emphasises the purely methodological significance of the concept 'energy,' in a great number of instances he himself fails to adhere to it. He every now and again converts 'energy' from a pure symbol of correlations between the facts of experience into the substance of experience, into the 'world stuff'" (Empirio-Monism, Bk. III, pp. xvi-xvii).

Energy is a pure symbol! After this Bogdanov may dispute as much as he pleases with the "empirio-symbolist" Yushkevich, with the "pure Machians," the empirio-criticists, etc.—from the standpoint of the materialist it is a dispute between a man who believes in a yellow devil and a man who believes in a green devil. For the important thing is not the differences between Bogdanov and the other Machians, but what they have in common, to wit: the idealist interpretation of "experience" and "energy," the denial of objective reality, adaptation to which constitutes human experience and the copying of which constitutes the only scientific "methodology" and scientific "energetics."

"It [Ostwald's energetics] is indifferent to the material of the world, it is fully compatible with both the old materialism and pan-psychism" (i.e., philosophical idealism?) (p. xvii). And Bogdanov departed from muddled energetics not by the materialist road but by the idealist road. . . . "When energy is represented as substance it is nothing but the old materialism minus the absolute atoms—materialism with a correction in the sense of the continuity of the existing" (ibid.). Yes, Bogdanov left the "old" materialism, i.e., the metaphysical materialism of the scientists, not for dialectical materialism, which he understood as little in 1906 as he did in 1899, but for idealism and fideism; for no educated representative of modern fideism, no immanentist, no "neo-criticist," and so forth, will object to the "methodological" conception of energy, to its interpretation as a "pure symbol of correlation of the facts of experience." Take Paul Carus, with whose mental make-up we have already become sufficiently acquainted, and you will find that this Machian criticises Ostwald in the very same way as Bogdanov : ". . . Materialism and energetics are exactly in the same predicament" (The Monist, Vol. XVII, 1907, No. 4, p. 536). "We are very little helped by materialism when we are told that everything is matter, that bodies are matter, and that thoughts are merely a function of matter, and Professor Ostwald's energetics is not a whit better when it tells us that matter is energy, and that the soul too is only a factor of energy" (p. 533).

Ostwald's energetics is a good example of how quickly a "new" terminology becomes fashionable, and how quickly it turns out that a somewhat altered mode of expression can in no way eliminate fundamental philosophical questions and fundamental philosophical trends. Both materialism and idealism can be expressed in terms of "energetics" (more or less consistently, of course) just as they can be expressed in terms of "experience," and the like. Energeticist physics is a source of new idealist attempts to conceive motion without matter—because of the disintegration of particles of matter which hitherto had been accounted non-disintegrable and because of the discovery of heretofore unknown forms of material motion.

← Chapter 5.4 →

4. The Two Trends in Modern Physics and English Spiritualism

In order to illustrate concretely the philosophical battle raging in present-day literature over the various conclusions drawn from the new physics, we shall let certain of the direct participants in the "fray" speak for themselves, and we shall begin with the English. The physicist Arthur W. Rücker defends one trend—from the standpoint of the natural scientist; the philosopher James Ward another trend—from the standpoint of epistemology.

At the meeting of the British Association held in Glasgow in 1901, A. W. Rücker, the president of the physics section, chose as the subject of his address the question of the value of physical theory and especially the doubts that have arisen as to the existence of atoms, and of the ether. The speaker referred to the physicists Poincaré and Poynting (an English man who shares the views of the symbolists, or Machians), who raised this problem, to the philosopher Ward, and to E. Haeckel's famous book and attempted to present his own views.[18]

"The question at issue," said Rücker, "is whether the hypotheses which are at the base of the scientihc theories now most generally accepted, are to be regarded as accurate descriptions of the constitution of the universe around us, or merely as convenient fictions." (In the terms used in our controversy with Bogdanov, Yushkevich and Co.: are they a copy of objective reality, of moving matter, or are they only a "methodology," a "pure symbol," mere "forms of organisation of experience"?) Rücker agrees that in practice there may prove to be no difference between the two theories; the direction of a river can be determined as well by one who examines only the blue streak on a map or diagram as by one who knows that this streak represents a real river. Theory, from the standpoint of a convenient fiction, will be an "aid to memory," a means of "producing order" in our observations in accordance with some artificial system, of "arranging our knowledge," reducing it to equations, etc. We can, for instance, confine ourselves to declaring heat to be a form of motion or energy, thus exchanging "a vivid conception of moving atoms for a colourless statement of heat energy, the real nature of which we do not attempt define." While fully recognising the possibility of achieving great scientific successes by this method, Rücker "ventures to assert that the exposition of such a system of tactics cannot be regarded as the last word of science in the struggle for the truth." The questions still force themselves upon us: "Can we argue back from the phenomenon displayed by matter to the constitution of matter itself; whether we have any reason to believe that the sketch which science has already drawn is to some extent a copy, and not a mere dia gram of the truth?"

Analysing the problem of the structure of matter, Rücker takes air as an example, saying that it consists of gases and that science resolves "an elementary gas into a mixture of atoms and ether. . . . There are those who cry 'Halt'; molecules and atoms cannot be directly perceived; they are mere conceptions, which have their uses, but cannot be regarded as realities." Rücker meets this objection by referring to one of numberless instances in the development of science: the rings of Saturn appear to be a continuous mass when observed through a telescope. The mathematicians proved by calculation that this is impossible and spectral analysis corroborated the conclusion reached on the basis of the calculations. Another objection: properties are attributed to atoms and ether such as our senses do not disclose in ordinary matter. Rücker answers this also, referring to such examples as the diffusion of gases and liquids, etc. A number of facts, observations and experiments prove that matter consists of discrete particles or grains. Whether these particles, atoms, are distinct from the surrounding "original medium" or "basic medium" (ether), or whether they are parts of this medium in a particular state, is still an open question, and has no bearing on the theory of the existence of atoms. There is no ground for denying a priori the evidence of experiments showing that "quasi-material substances" exist which differ from ordinary matter (atoms and ether). Particular errors are here inevitable, but the aggregate of scientific data leaves no room for doubting the existence of atoms and molecules.

Rücker then refers to the new data on the structure of atoms, which consist of corpuscles (electrons) charged with negative electricity, and notes the similarities in the results of various experiments and calculations on the size of molecules: the "first approximation" gives a diameter of about 100 millimicrons (millionths of a millimetre). Omitting Rücker's particular remarks and his criticism of neo-vitalism,[20] we quote his conclusions:

"Those who belittle the ideas which have of late governed the advance of scientific theory, too often assume that there is no alternative between the opposing assertions that atoms and the ether are mere figments of the scientific imagination, and that, on the other hand, a mechanical theory of the atoms and the ether, which is now confessedly imperfect, would, if it could be perfected, give us a full and adequate representation of the underlying realities. For my part I believe that there is a via media." A man in a dark room may discern objects dimly, but if he does not stumble over the furniture and does not walk into a looking-glass instead of through a door, it means that he sees some things correctly. There is no need, therefore, either to renounce the claim to penetrate below the surface of nature, or to claim that we have already fully unveiled the mystery of the world around us. "It may be granted that we have not yet framed a consistent image either of the nature of the atoms or of the ether in which they exist, but I have tried to show that in spite of the tentative nature of some of our theories, in spite of many outstanding difficulties, the atomic theory unifies so many facts, simplifies so much that is complicated, that we have a right to insist—at all events until an equally intelligible rival hypothesis is produced—that the main structure of our theory is true; that atoms are not merely aids to puzzled mathematicians, but physical realities."

That is how Rücker ended his address. The reader will see that the speaker did not deal with epistemology, but as a matter of fact, doubtless in the name of a host of scientists, he was essentially expounding an instinctive materialist standpoint. The gist of his position is this: The theory of physics is a copy (becoming ever more exact) of objective reality. The world is matter in motion, our knowledge of which grows ever more profound. The inaccuracies of Rücker's philosophy are due to an unnecessary defence of the "mechanical" (why not electromagnetic?) theory of ether motions and to a failure to understand the relation between relative and absolute truth. This physicist lacks only a knowledge of dialectical materialism (if we do not count, of course, those very important social considerations which induce English professors to call themselves "agnostics").

Let us now see how the spiritualist James Ward criticised I this philosophy: "Naturalism is not science, and the mechanical theory of Nature, the theory which serves as its foundation, is no science either. . . . Nevertheless, though Naturalism and the natural sciences, the Mechanical Theory of the Universe and mechanics as a science are logically distinct, yet the two are at first sight very similar and historically are very closely connected. Between the natural sciences and philosophies of the idealist (or spiritualist) type there is indeed no danger of confusion, for all such philosophies necessarily involve criticism of the epistemological assumptions which science unconsciously makes."[19] True! The natural sciences unconsciously assume that their teachings reflect objective reality, and only such a philosophy is reconcilable with the natural sciences! ". . . Not so with Naturalism, which is as innocent of any theory of knowledge as science itself. In fact Naturalism, like Materialism, is only physics treated as metaphysics. . . . Naturalism is less dogmatic than Materialism, no doubt, owing to its agnostic reservation as to the nature of ultimate reality; but it insists emphatically on the priority of the material aspect of its Unknowable."

The materialist treats physics as metaphysics! A familiar argument. By metaphysics is meant the recognition of an objective reality outside man. The spiritualists agree with the Kantians and Humeans in such reproaches against materialism. This is understandable; for without doing away with the objective reality of things, bodies and objects known to everyone, it is impossible to clear the road for "real conceptions" in Rehmke's sense! . . .

"When the essentially philosophical question, how best to systematise experience as a whole [a plagiarism from Bogdanov, Mr. Ward!], arises, the naturalist . . . contends that we must begin from the physical side. Then only are the facts precise, determinate, and rigorously concatenated: every thought that ever stirred the human heart . . . can, it holds, be traced to a perfectly definite redistribution of matter and motion. . . . That propositions of such philosophic generality and scope are legitimate deductions from physical science, few, if any, of our modern physicists are bold enough directly to maintain. But many of them consider that their science itself is attacked by those who seek to lay bare the latent metaphysics, the physical realism, on which the Mechanical Theory of the Universe rests. . . . The criticism of this theory in the preceding lectures has been so regarded [by Rücker]. . . . In point of fact my criticism [of this "metaphysics," so detested by all the Machians too] rests throughout on the expositions of a school of physicists—if one might call them so—steadily increasing in number and influence, who reject entirely the almost medieval realism. . . . This realism has remained so long unquestioned, that to challenge it now seems to many to spell scientific anarchy. And yet it surely verges on extravagance to suppose that men like Kirchhoff or Poincaré—to mention only two out of many distinguished names—who do challenge it, are seeking 'to invalidate the methods of science.' . . . To distinguish them from the old school, whom we may fairly term physical realists, we might call the new school physical symbolists. The term is not very happy, but it may at least serve to emphasise the one difference between the two which now specially concerns us. The question at issue is very simple. Both schools start, of course, from the same perceptual experiences; both employ an abstract conceptual system, differing in detail but essentially the same; both resort to the same methods of verification. But the one believes that it is getting nearer to the ultimate reality and leaving mere appearances behind it; the other believes that it is only substituting a generalised descriptive scheme that is intellectually manageable, for the complexity of concrete facts. . . . In either view the value of physics as systematic knowledge about [Ward's italics] things is unaffected; its possibilities of future extension and of practical application are in either case the same. But the speculative difference between the two is immense, and in this respect the question which is right becomes important."

The question is put by this frank and consistent spiritualist with remarkable truth and clarity. Indeed, the difference between the two schools in modern physics is only philosophical, only epistemological. Indeed, the basic distinction is only that one recognises the "ultimate" (he should have said objective) reality reflected by our theory, while the other denies it, regarding theory as only a systematisation of experience, a system of empirio-symbols, and so on and so forth. The new physics, having found new aspects of matter and new forms of its motion, raised the old philosophical questions because of the collapse of the old physical concepts. And if the people belonging to "intermediate" philosophical trends ("positivists," Humeans, Machians) are unable to put the question at issue distinctly, it remained for the outspoken idealist Ward to tear off all veils.

". . . Sir A. W. Rücker . . . devoted his Inaugural Address to a defence of physical realism against the symbolic inter pretations recently advocated by Professors Poincaré and Poynting and by myself" (pp. 305-06; and in other parts of his book Ward adds to this list the names of Duhem, Pearson and Mach; see Vol. II, pp. 161, 63, 57, 75, 83, etc.).

". . . He [Rücker] is constantly talking of 'mental pictures,' while constantly protesting that atoms and ether must be more than these. Such procedure practically amounts to saying: In this case I can form no other picture, and therefore the reality must be like it. . . . He [Rücker] is fair enough to allow the abstract possibility of a different mental picture. . . . Nay, he allows 'the tentative nature of some of our theories'; he admits 'many outstanding difficulties.' After all, then, he is only defending a working hypothesis, and one, moreover, that has lost greatly in prestige in the last half century. But if the atomic and other theories of the constitution of matter are but working hypotheses, and hypotheses strictly confined to physical phenomena, there is no justification for a theory which maintains that mechanism is fundamental everywhere and reduces the facts of life and mind to epiphenomena—makes them, that is to say, a degree more phenomenal, a degree less real than matter and motion. Such is the mechanical theory of the universe. Save as he seems unwittingly to countenance that, we have then no quarrel with Sir Arthur Rücker" (pp. 314-15).

It is, of course, utterly absurd to say that materialism ever maintained that consciousness is "less" real, or necessarily professed a "mechanical," and not an electromagnetic, or some other, immeasurably more complex, picture of the world of moving matter. But in a truly adroit manner, much more skilfully than our Machians (i.e., muddled idealists), the outspoken and straightforward idealist Ward seizes upon the weak points in "instinctive" natural-historical materialism, as, for instance, its inability to explain the relation of relative and absolute truth. Ward turns somersaults and declares that since truth is relative, approximate, only "tentative," it cannot reflect reality! But, on the other hand, the question of atoms, etc., as "a working hypothesis" is very correctly put by the spiritualist. Modern, cultured fideism (which Ward directly deduces from his spiritualism) does not think of demanding anything more than the declaration that the concepts of natural science are "working hypotheses." We will, sirs, surrender science to you scientists provided you surrender epistemology, philosophy to us—such is the condition for the cohabitation of the theologians and professors in the "advanced" capitalist countries.

Among the other points on which Ward connects his epistemology with the "new" physics must be counted his deter mined attack on matter. What is matter and what is energy?—asks Ward, mocking at the plethora of hypotheses and their contradictoriness. Is it ether or ethers?—or, perhaps, some new "perfect fluid," arbitrarily endowed with new and improbable qualities? And Ward's conclusion is: " . . . we find nothing definite except movement left. Heat is a mode of motion, elasticity is a mode of motion, light and magnetism are modes of motion. Nay, mass itself is, in the end, supposed to be but a mode of motion of a something that is neither solid, nor liquid nor gas, that is neither itself a body nor an aggregate of bodies, that is not phenomenal and must not be noumenal, a veritable apeiron [a term used by the Greek philosophers signifying: infinite, boundless] on which we can impose our own terms" (Vol. I, p. 140).

The spiritualist is true to himself when he divorces motion from matter. The movement of bodies is transformed in nature into a movement of something that is not a body with a constant mass, into a movement of an unknown charge of an unknown electricity in an unknown ether—this dialectics of material transformation, performed in the laboratory and in the factory, serves in the eyes of the idealist (as in the eyes of the public at large, and of the Machians) not as a confirmation of materialist dialectics, but as evidence against materialism: " . . . The mechanical theory, as a professed explanation of the world, receives its death-blow from the progress of mechanical physics itself" (p. 143). The world is matter in motion, we reply, and the laws of its motion are reflected by mechanics in the case of moderate velocities and by the electromagnetic theory in the case of great velocities. "Extended, solid, indestructible atoms have always been the stronghold of materialistic views of the universe. But, unhappily for such views, the hard, extended atom was not equal to the demands which increasing knowledge made upon it" (p. 144). The destructibility of the atom, its inexhaustibility, the mutability of all forms of matter and of its motion, have always been the stronghold of dialectical materialism. All boundaries in nature are conditional, relative, movable, and express the gradual approximation of our mind towards the knowledge of matter. But this does not in any way prove that nature, matter itself, is a symbol, a conventional sign, i.e., the product of our mind. The electron is to the atom as a full stop in this book is to the size of a building 200 feet long, 100 feet broad, and 50 feet high (Lodge); it moves with a velocity as high as 270,000 kilometres per second; its mass is a function of its velocity; it makes 500 trillion revolutions in a second—all this is much more complicated than the old mechanics; but it is, nevertheless, movement of matter in space and time. Human reason has discovered many amazing things in nature and will discover still more, and will thereby increase its power over nature. But this does not mean that nature is the creation of our mind or of abstract mind, i.e., of Ward's God, Bogdanov's "substitution," etc.

"Rigorously carried out as a theory of the real world, that ideal [i.e., the ideal of "mechanism"] lands us in nihilism: all changes are motions, for motions are the only changes we can understand, and so what moves, to be understood, must itself be motion" (p. 166). "As I have tried to show, and as I believe, the very advance of physics is proving the most effectual cure for this ignorant faith in matter and motion as the inmost substance rather than the most abstract symbols of the sum of existence. . . . We can never get to God through a mere mechanism" (p. 180).

Well, well, this is exactly in the spirit of the Studies "in" the Philosophy of Marxism ! Mr. Ward, you ought to address yourself to Lunacharsky, Yushkevich, Bazarov and Bogdanov. They are a little more "shamefaced" than you are, but they preach the same doctrine.

← Chapter 5.5 →

5. The Two Trends in Modern Physics, and German Idealism

In 1896, the well-known Kantian idealist Hermann Cohen, with unusually triumphant exultation, wrote an introduction to the fifth edition of the Geschichte des Materialismus, the falsified history of materialism written by F. Albert Lange. "Theoretical idealism," exclaims Cohen (p. xxvi), "has already begun to shake the materialism of the natural scientists, and perhaps in only a little while will defeat it completely." Idealism is permeating (Durchwirkung) the new physics. "Atomism must give place to dynamism. . . ." "It is a remarkable turn of affairs that research into the chemical problem of substance should have led to a fundamental triumph over the materialist view of matter. Just as Thales performed the first abstraction of the idea of substance, and linked it with speculations on the electron, so the theory of electricity was destined to cause the greatest revolution in the conception of matter and, through the transformation of matter into force, bring about the victory of idealism" (p. xxix).

Hermann Cohen is as clear and definite as James Ward in pointing out the fundamental philosophical trends, and does not lose himself (as our Machians do) in petty distinctions between this and that energeticist, symbolist, empirio-criticist, empirio-monist idealism, and so forth. Cohen takes the fundamental philosophical trend of the school of physics that is now associated with the names of Mach, Poincaré and others and correctly describes this trend as idealist. "The transformation of matter into force" is here for Cohen the most important triumph of idealism, just as it was for the "ghost-seeing" scientists—whom J. Dietzgen exposed in 1869. Electricity is proclaimed a collaborator of idealism, because it has destroyed the old theory of the structure of matter, shattered the atom and discovered new forms of material motion, so unlike the old, so totally uninvestigated and unstudied, so unusual and "miraculous," that it permits nature to be presented as non-material (spiritual, mental, psychical) motion. Yesterday's limit to our knowledge of the infinitesimal particles of matter has disappeared, hence—concludes the idealist philosopher—matter has disappeared (but thought remains). Every physicist and every engineer knows that electricity is (material) motion, but nobody knows clearly what is moving, hence—concludes the idealist philosopher—we can dupe the philosophically uneducated with the seductively "economical" proposition: let us conceive motion without matter. . . .

Hermann Cohen tries to enlist the famous physicist Heinrich Hertz as llis ally. Hertz is ours—he is a Kantian, we sometimes find him admitting the a priori, he says. Hertz is ours, he is a Machian—contends the Machian Kleinpeter—for in Hertz we have glimpses of "the same subjectivist view of the nature of our concepts as in the case of Mach."[21] This strange dispute as to where Hertz belongs is a good example of how the idealist philosophers seize on the minutest error, the slightest vagueness of expression on the part of renowned scientists in order to justify their refurbished defence of fideism. As a matter of fact, Hertz's philosophical preface to his Mechanik[22] displays the usual standpoint of the scientist who has been intimidated by the professorial hue and cry against the "metaphysics" of materialism, but who nevertheless cannot overcome his instinctive conviction of the reality of the external world. This has been acknowledged by Kleinpeter himself, who on the one hand casts to the mass of readers thoroughly false popularly-written pamphlets on the theory of knowledge of natural science, in which Mach figures side by side with Hertz, while on the other, in specifically philosophical articles, he admits that "Hertz, as opposed to Mach and Pearson, still clings to the prejudice that all physics can be explained in a mechanistic way,"[23] that he retains the concept of the thing-in-itself and "the usual standpoint of the physicists," and that Hertz still adheres to "a picture of the universe in itself," and so on.[24]

It is interesting to note Hertz's view of energetics. He writes: "If we inquire into the real reason why physics at the present time prefers to express itself in terms of energetics, we may answer that it is because in this way it best avoids talking about things of which it knows very little. . . . Of course, we are now convinced that ponderable matter consists of atoms; and in certain cases we have fairly definite ideas of the magnitude of these atoms and of their motions. But the form of the atoms, their connection, their motions in most cases, all these are entirely hidden from us. . . . So that our conception of atoms is therefore in itself an important and interesting object for further investigations, but is not particularly adapted to serve as a known and secure foundation for mathematical theories" (op. cit., Vol. III, p. 21). Hertz expected that further study of the ether would provide an explanation of the "nature of traditional matter . . . its inertia and gravitational force" (Vol. I, p. 354).

It is evident from this that the possibility of a non-materialist view of energy did not even occur to Hertz. Energetics served the philosophers as an excuse to desert materialism for idealism. The scientist regards energetics as a convenient method of expressing the laws of material motion at a period when, if we may so express it, physicists had left the atom but had not yet arrived at the electron. This period is to a large extent not yet at an end; one hypothesis yields place to another; nothing whatever is known of the positive electron; only three months ago (June 22, 1908), Jean Becquerel reported to the French Academy of Science that he had succeeded in discovering this "new component part of matter" (Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Sciences, p. 1311). How could idealist philosophy refrain from taking advantage of such an opportunity, when "matter" was still being "sought" by the human mind and was therefore no more than a "symbol," etc.